Hello friends, familiar and new, and welcome to a house in a hamlet in a forest. I’m Jan and I hold spaces for those on journeys of transformation. I believe story is powerful and that the earth offers healing through our daily connection and herbal allies. My Sunday posts are always free. Let’s create a little alchemy together.

You might find this easier to read in the app or online as some mail providers will cut off the text.

Encounters — always we are searching to know, to understand the other, to recognise the creature that might tell us something about our own reflection — human and more than than human, ancestral and present, like and unlike us...

Reading is a way of making sense of our world — external and internal and in each season's reading I notice threads that wind through seemingly disparate books. From a coming of age novella to a struggle for survival, from poetry of winged creatures to a novel of mythic horror tht digs deep into gender, from poetry that examines how women have been 'constructed' as witches to memoir that seeks to 'construct' a nervous system in the face of racist stereotyping, from how we make art to how we eat and ritualise food... here are narratives that give us access to deep stories of creatures whose hearts beat with love, grief, hope, fear and more...

Fiction

Tessa Hadley, The Party

I read this novella on a restful day between cooking and a film with family and loved it. Tessa's writing is so fluid and unobtrusive. We slip into the world she creates with ease and the sensory details reveal rich interior worlds without her ever pointing this out.

The Party is set in post-war Bristol, a place I lived for 6 years and where 3 of my children were born, so I enjoyed the place-spotting. Evelyn and Moira are sisters, one an art student the other an undergraduate studying French. Their home is conventional, middle-class and faintly oppressive -- a world where everything of import goes unsaid.

They are on the cusp of adulthood and independence and Evelyn, the younger sister, opens the story on her way to a party that her parents would not allow. A semi-ruined pub in the docks, a jazz band, her sister, Moira, two-years older and more confident, already there.

They attract the attention of two men who do not belong to this anarchic, bohemian group. Upper-class, insistent and sophisticated, Paul and Sinden offer connections and worldliness beyond the sisters' experiences. They offer a party that will change everything.

Cynon Jones, The Cove

Spare, lyrical, and with the suppleness of prose poetry, The Cove is a deceptively simple story that is profoundly moving and poignant. A man sets out to sea to fish and leaves a note: 'Pick salad x.'

His pregnant wife, addressed in an implicating second person in the tiny prologue (reminiscent of the opening of Cormac McCarthy's Suttree) goes down to the beach to wash her hands after finding a dead pigeon. There, other signs are strewn: a search party for a missing child; a doll washed up.

Out at sea, the man senses lightning before it strikes, watches the storm roll in -- the metallic sheen of the water, the glow of the leaden-edged clouds. And then

One word repeated. no, no, no.

When it hits him there is a bright white light.

And then we are back, earlier in the day -- the details of the catch, the boat, the things he has done before, the routines... shattered... waking lying on his back in the boat, not knowing what has happened, shocked, injured, far out to sea...

What follows is terrible and beautiful. The intricacies of hope and resilience threaded with frailty and fear. The struggle for survival is elemental, mesmerising, and startling to the last exquisite word.

Olga Tokarczuk, The Empusium, a health resort horror story

I am in awe of Olga Tokarczuk — her range of references, the skill with which a narrative quietly builds to something beyond extraordinary, the breath-taking inventiveness and the wit — sharp and lively and subversive.

Mieczysław Wojnicz has been weak, sickly and 'different' all his life, constantly failing to be 'the man' his father wants. In 1913 he is sent to a sanatorium for a treatment for the lung condition that has plagued him for years. The sanatorium, based on the real one set up by Doctor Brehmer at the end of the 1870s and also the location of Thomas Mann's the Magic Mountain is a place of repetitive and tedious daily treatments that Wojnicz finds intrusive.

But life at the Guesthouse for Gentlemen, a cheaper place to stay than the main Kurhaus, is not unpleasant. He befriends the only other young patient, Thilo, and enjoys the conversation of the men, despite often finding himself an outsider, especially when the conversation turns to the inferiority of women, with their wandering wombs and lack of rational faculties. And even more especially when, after several glasses of the distinctive and potent local herbal liqueur, the conversation fills with sexual inuendo that leaves Wojnicz feeling naive and uncomfortable.

We know from the outset that this is a 'horror story', but the strangeness creeps up on us slowly. There is more to this liqueur than its affect on inhibitions. What is the truth about the untimely death of the guesthouse owner's wife? Why is Wojnicz so fascinated by her empty room and is he really hearing pigeons up there in the attic? What is the meaning of the strange chair in another part of the attic? And who are the other narrator's of this book — the mysterious, omnipresent 'we'?

The questions mount and there is an unsettling ethos across the village and in the strange forest beyond with its unworldly sculptures of female figures in stone, branches and moss... The twist, when it comes, is so much more than expected. As wry and funny as the scene that leads to its reveal is dark and bloody. And at last we realise who has been telling this story all along.

An utterly brilliant novel that digs deeply into gender and how we relate to the elemental world around us, and does so with Tokarczuk's signature mischievous but humane bravura.

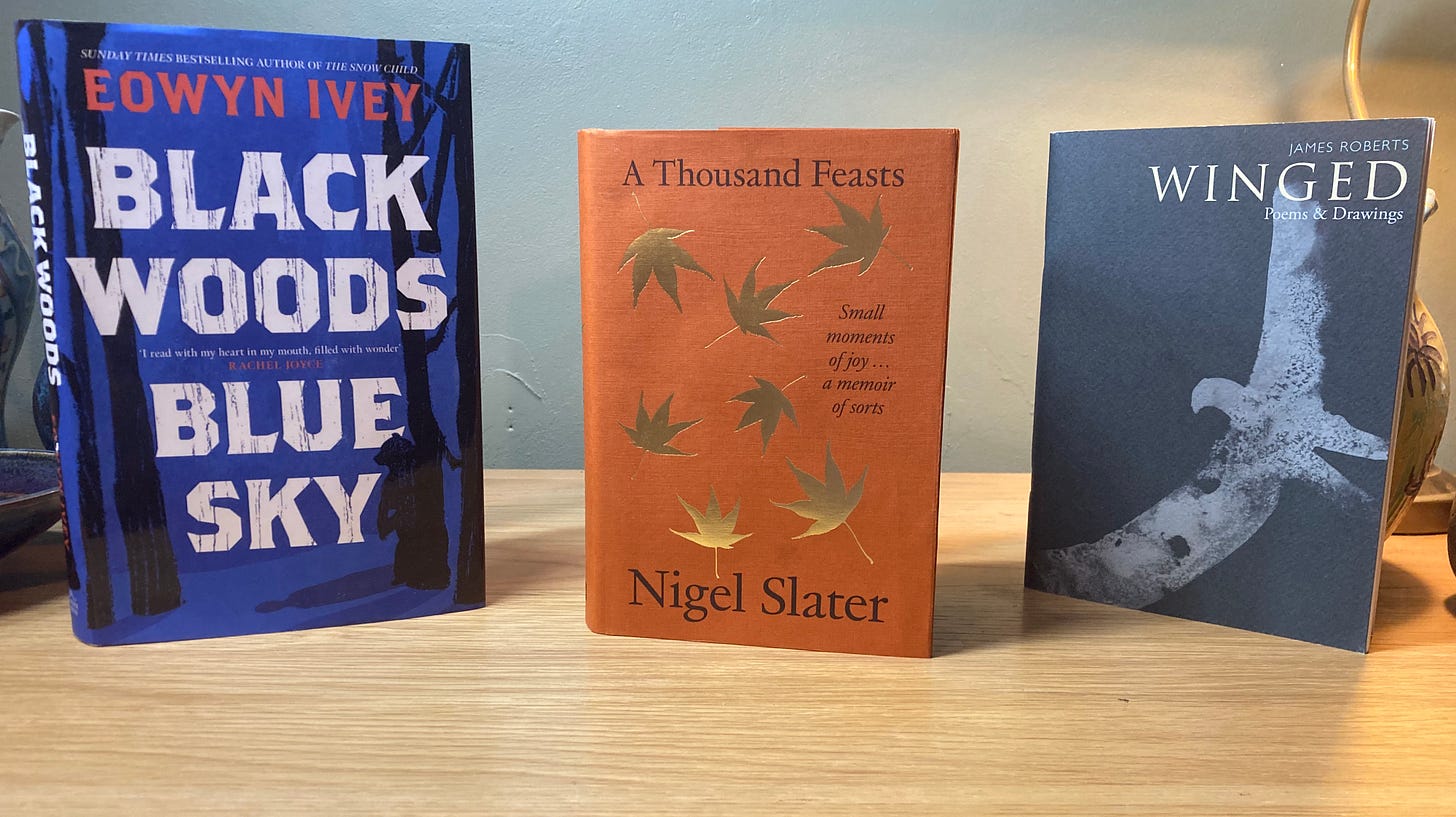

Bernard Schlink, The Granddaughter

I've loved previous books by Bernard Schlink and was mesmerised by the story of Kaspar Wettner, an ageoing bookseller in Berlin, whose life takes him on an unexpected search for his wife's daughter, given up at birth, and leads him into a relationship with Sigrun, the granddaughter being raised in a völkisch community. In the parallel society the neo-Nazi dream is alive and well. Kaspar aspires to change Sigrun's outlook. She's an intelligent, gifted young woman who loves literature and music and soon grows fond of her new-found grandfather. But can fifteen years of constant conditioning be so easily overcome? And is Kaspar over-simplifying or even stereotypying his views of Sigrun's family and community? More crucially, is Sigrun on a path that can only lead to catastrophe?

Without preaching, Schlink delivers a fascinating glimpse into the ongoing trauma of a country coming to terms with its past -- not only in World War II, but in the aftermath of division and Reunification. The distrust and fear between different segments of society is palpable and all-too recognisable across Western 'civilisation', with it's propensity to scapegoat the 'other' whether that 'other' is a different region, group, religion, gender orientation or immigrants... or all of the above.

The Granddaughter is humane, shocking, enlightening and faces what it means to love a country without resorting to hating the other. As Kaspar says,

I think you can only be proud of something you’ve actually done. But maybe it can be looked at differently. [...] I love my country, I’m glad that I speak its language, that I understand its people, that it’s familiar to me. I don’t have to be proud that I’m German; it’s enough for me that I’m glad of it.

The end, which is not fully resolved (and there's no harm in that) had me on tenterhooks but is not without a glimmer of hope.

Louise Erdrich, The Mighty Red

The Mighty Red references a river in North Dakota around which lives are lived and in which death waits.

Crystal Frechette, a trucker, hauling sugar beets as she looks for signs and places her hopes in her daughter, Kismet Poe is about to have her life turned upside-down. Kismet, just finishing High School is clever, but open to the gaping needs of others. She might be in love with Hugo, an autodidact who doesn't fit easily into society but knows where he is headed . But then there is Gary, her school’s quarterback, who seems to have a guardian angel despite his frequent brushes with danger and death. But also comes with demons — a story that it takes nearly the whole book to reveal, but is constantly, hauntingly foreshadowed.

Gary believes only marriage to Kismet will save him. And his mother, Winnie, carrying her own demons after marrying into the family that presided over demolishing her family' farm in a previous economic crash, is determined that her son will get what he wishes.

This is a story of extraordinary, ordinary individuals, but it's also a story about the systems that reach into people's lives and wreak havoc. It's 2008 and a comunity already struggling with poverty is plunged into wider economic meltdown.

Into the mix, Kismet's father, Martin, who has been speculating with the Church's renovation fund in hopes of growing it, is facing how he is going to handle the whole amount disappearing in a stock crash.

The stakes mount for everyone. The precariousness of lives is breath-taking. But if it sounds heavy, it's not. The characters, who will make you love them or scream at them, are so real. And there is constant wit and gentle parody of human foibles. The local book club, making its way through Eat Pray Love and The Road, provides comic relief without dumbing anything down.

And to add another layer, this is a story not only of individuals and societal systems, but also of heritage and land. How do mixed-heritage Native people hold on to traditions? How do impoverished communities and small farmers make a living in a climate of agri-businesses that are short-term, reliant on toxins and existing alongside brutal practices like fracking?

Written in excellent prose, the polluted Red River, is a 'brown muscle of water', for example, Erdrich excavates huge questions, including putting a lens on how abusive relationships can work with slow lethality, to produce a story that is compelling and deeply satisfying.

Pascal Mercier, Night Train to Lisbon

I knew Night Train to Lisbon first as a film and loved it. But the novel digs so much deeper, both in the range of ideas it explores and inthe depth of characterisation. I read it mostly on trains during a recent journey and it was the perfect rhythm, mirroring the metaphor that runs through a book that delves into our concepts of time and space. But it also does so much more.

When Raimund Gregorius, an entirely predictable philologist who teaches Latin, Greek and Hebrew at a Swiss high school, has a strange and brief encounter with a young woman on a bridge, he is left with a book of philosophical musings by a Portuguese author — a book that changes his life. Determined to learn more of the life of Amadeu de Prado, Gregorius travels to Lisbon where he begins to piece together the complex story of this man... son of a highcourt judge, from an aristoctratic family, a brilliant thinker, skillful doctor and tortured soul.

Against the backdrop of brutal regime of Portugal’s dictator, Antonio Salazar, we meet Prado through the stories others tell of him. His adoring sister who was jealous of his time and attention and for whom time has stopped. His once fiercely loyal friend and now embittered ageing pharmacist, Jorge O'Kelly. Survivor of torture during the resistance, João Eça. His friend and confidante from schooldays, Maria and the woman who might have been the love of his life, Estefania... Each add to the puzzle as Gregorius reads Prado's text, searching for answers to his own life.

Had he perhaps missed a possible life, one he could easily have lived with his abilities and knowledge?

The writing is elegant and poetic. It's a big book, full of questions and characters who are deeply flawed and as deeply sympathetic. I made pages of notes and quotes in my journal as I read it (mostly on trains while travelling to a conference) and it felt like a mirror held up the reader as well as an extraordinary and immersive story. The film is beautiful and haunting, the book even more so.

Yoko Tawada, Memoirs of a Polar Bear

In this triptych of memoirs across three generation we're in strange territory. The first bear, injured in the circus, turns writer after she's assigned a desk job when she can no longer perform. Her life becomes sequence of mind-numbing, useless conferences from which writing is an escape. Fleeing Russia, she moves to Germany but her problems are not over — her publisher is unscrupulous and exploitative and her writing has unforseen consequences.

If the book sounds like it requires a suspension of disbelief, it certainly does, but each section is also deeply concerned with issues of justice. In the first part the cruelty of how bears are trained, climate change, the struggles of life in Russia and the sheer wasteful idiocy of how management operates in business are all explored. And from the perspective of a bear we are spared didacticism, instead seeing the human world through very different eyes.

The second section is the story of the bear's daughter, Tosca — a performer in an East Berlin circus whose story is told by her trainer and soulmate, Barbara. They share a language that is instinctive and sensory, but their deep love is intimately tied up with training and performance.

When Tosca's twin cubs are born she wants nothing to do with them and the surviving son, based on a real zoo bear, Knut, becomes a public cause, but Knut's relationship with his keeper and his 'cute' appeal sour as he grows.

Their bond is touching, and their communication is instinctive as well as tactile. Their act is called “The Kiss”. The tenderness they share is contrasted with the more bombastic approach of the other nine polar bears who had been recruited. These bears quickly formed a union “and could deliver political speeches in fluent German.”

It may be that Tawada is exploring love at its most devouring, manipulative and dominating. The bonds the animals establish with humans are based on them being trained to perform unnatural tricks. But then, as is pointed out, the animals are also described as having come from distant lands when many of them have been born in the zoo in which they are held and will never experience their natural habitat. Tosca is complex, her love for Barbara is deep and in time she will mourn her. Yet when she is delivered of twin cubs, she rejects them and does not react when they are removed from her enclosure. One of them dies. The other becomes very famous, initially for having survived, and then for having died suddenly.

Strange, thought-provoking and often emotionally intense, the novel asks us to reconsider our perspective on the world.

Eowyn Ivey, Black Wood, Blue Sky

I was riveted by this novel, as I was previously to Eowyn Ivey's The Snow Child. Set in Alaska, Birdie is a struggling young single mother trying, with some notable lapses, to raise 6-year-old Emaleen between shifts in a the bar of the local lodge. In her short breaks, Birdie, whose own mother abandoned her, sits on a picnic table gazing into the mountains and longing for a different life.

When she begins to develop a relationship with Arthur, who is strange, quiet and speaks only in present tense, explaining that time is cyclic and all times are now... Birdie senses a way out of life of drudgery, low expectations and bouts of alcohol and drugs to numb the despair.

Others in the community are more doubtful. Della, her employer, worries about how Birdie and Emaleen will adapt to living in a mountain cabin without electricity, running water... Warren, Arthur's adoptive father, who knows more about the darkness in Arthur than he is revealing, convinces himself that love will overcome all. And Syd, the local professor, quoting Proust, wishes her blue sky when the woods are black.

On the mountain, life is both hard and freeing. Despite Birdie's frustrations with Arthur's frequent and sometimes long mysterious absences... despite the puzzle of why Arthur eats hardly any of the food Birdie prepares... for a sweet moment life becomes a dream, privations and all, and when Arthur says,

“I am loving you,” she muses: “As if love, once it came into existence, radiated backward and forward, encompassing all of time.”

But Arthur's secret is raw and savage and as time goes on his ability to manage in this small family strains dramatically and with devastating consequences.

And yet... in spite of the loss and grief, the book returns to love, to the nature of forgiveness, to how the events that make us are so often not those we would have chosen to live.

Poetry

Catherine Hyde, Darkling, The Owl's Song

An exquisite artist's book featuring rich, dense artwork of an owl's journey towards his mate as well as the creatures and landscacpe along the way, the long poem that threads the images together is as sensual and alive as the gorgeous images. I awaited this enchanted book eagerly and find myself going back and back to it. At night I listen to a pair of owls answering one another in the woods around our garden, which made the owls here even more evocative. The male owl listens for the answering -- kee witt kee witt to his hooo hooo hooo, honing in through the vibrant night.

I turn

to the old orchard

where she hunt:

a ghost glimmering

sweet heart of the moon.

Sweeping between trees,

a beating clock of claw and feather,

hush winged, in halflight.

She screams

shattering night.

Derek Jarman, A Finger in the Fish's Mouth

Published posthumously as a facsimile of an earlier limited edition collection, A Finger in the Fish's Mouth brings together postcards from Jarman's private collection with short lyric poems. The postcards travel across locations Jarman journeyed to and those he never visited but made some connection with, like those of Egypt. Each is rendered in a green monochrome, a slightly livid lime tint that gives the book an other-worldliness. As Jarman says:

Postcards don't just communicate the world: they change it. Connecting there to here, they offer opium dreams of possibility.

The poems range widely — travel and freedom, sex, allusions to Blake, the Beats , Jean Cocteau and classical literature, many references to landscape, night and the moon... The best poems are the shortest pieces or those with closely observed details placed alongside something slightly strange, a shift in perspective...

Poem 1

In the common silence

of the world

the white poppies of

my love are dancing

And always there is a sense of loss

now in these our letters

we are building a marble monument

[...]

we have proven our loss

The trip is over

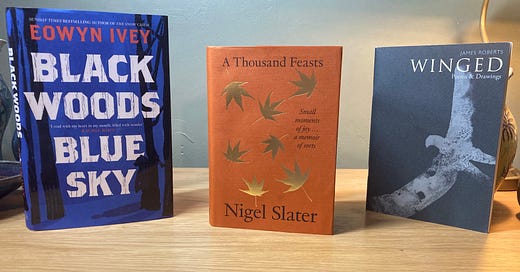

James Roberts, Winged

From the restrained and crafted production of the pamphlet to the evocative, immersive ink drawings of birds to the poetry lines brimming with grace and tenderness, Winged is a thing of beauty.

The fourteen poems, each paired with an exquisite drawing, work magic as they are read. There is so much poetry that is crafted, clever, knowing. So much that keys into particular trends. And that is not always to be decried. But this is poetry with a beating soul and soaring heart from an artist who pays attention to the smallest movements, the deepest resonances.

Without sentiment of show we wing into an inner world while learning so much of these fourteen marvelous creatures of flight.

From 'Swallow'

In days swallows will return

carrying an unseen Africa.

Will all this be familiar to them as to me?

Beneath roof beams a nest intact

still scented with last year's brood.

Lives they tended to so furiously

gone forever to endlessly return.

Everything close and miles away,

the distances contained in a wing.

If you don't already subscribe to James Roberts' substack now is the time and the pamphlet is available from his website along with stunning artwork.

Danez Smith, Bluff

For Smith poetry is an act of resistance, but always with an awareness of the limits of language and the limits of the page. Those limits are pushed hard — the pieces are complex — emotionally, conceptually and in their formal structures. And this is not poetry for the faint-hearted.

A non-binary poet of colour, silencing is a familiar theme, and in this collection is made more acute by being written after the silence of Covid lockdowns and in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests in Minneapolis, where Smith lives.

The combination is, as Joelle Taylor has commented, 'breathtaking. How do we go on making art in the face of brutal oppression? The voice is variously outraged and vulnerable, raw and eloquent, painfully honest and persistently hopeful.

The pieces on the page are sometimes lyric, sometimes pushed against the right hand margin, sometimes imagistic (including a QR code some formal invention that takes concrete work in new directions.

I often find poetry that has an agenda on us or poetry that too-easily believes it can save the world to be unconvincing. But this is not what Danez Smith is doing. They are skilful, imaginative and courageous. As they say in ars poetica:

wherever you are reading this

is the future to me, which means

tomorrow is still coming, which means

today still lives, which means

there is still time

to make more alive

which means there is still

poetry.

Prophetic, moving and defiant work from a startling voice.

Beverley Bie Brahic, Apple Thieves

This elegant collection came as a gift from a friend who'd heard the author read in Paris. The poetry is deft and thoughtful. The metaphors are subtle and the observation acute. Bie Brahic grew up in Canada, taught in Ghana and now lives in France, moving between Paris and the countryside. The range of reference is deepened not only by geography but also by her work as a translator with several poems drawing on influences, including a clutch of pieces after works by Giacomo Leopardi.

But this is not obscure or abstract work. The poems are sensual and supple and revolve around daily life and the small events that are actually vital in how we relate and remember and love. Tenderness and compassion run through the poems. It's exemplified in the title poem 'Apple Thieves' as a widower cherishes the trees planted by his wife or in 'The Cardigan', a story of how we make and mend and how meaning weaves into ordinary things.

Moments that could go unnoticed are captured, as when to the poet briefly encounters a chained elephant

I caught her eye and she, I felt, held mine

As if we had something to say

If only we could find the words.

'When the Circus Came to Town'

And the smallest snail shell takes on significance

I can balance it

On the palm of my hand

Trace the elegant

Mathematical spirals

Slip into the

Voluptuous interior

Of this empty house

A nudge will set rocking

Almost indefinitely,

'Exoskeleton'

Tim Tim Cheng, The Tattoo Collector

In this inventive and probing debut collection the poems move from lyric to prose, from pale grey pieces that incorporate words in bold to open field... they use Chinese characters, both Mandarin and Canotonese and a poem titled 'The Tattoo Collector' occurs several times across the collection.

Family history, migration, politics and protest weave through the poems. There's movement East to West... Hong Kong, Scotland, London. And with the movement the body shifts, becomes the page and on which so much is sharply written. some of it permeating so deep that new metaphors bloom in blood and ink.

Language is interrogated and expanded here and there's a extraordinary balance between the radical and the intimate, the tender, acute observations and the large narrative. Skin, language, place, self... all are laid bare, inscribed, changed.

Happiness

comes like an ambulance

you hear from a distance.

You were once told that

you don't miss a person.

You miss the period they represent.

What they were trying to say was

we're over.

'The Tattoo Collector'

And in 'Deluge' which begins and end in rain:

I could've been one of the casualties

had mother not moved to Hong Kong,

where ridicules on anything Chinese,

deaths included, are the few things

we could clam control.

About Zhengzhou, a place that shares

my absent father's surname,

all I know is a singer's raspy voice,

censored, mulling over the loss

of someone, somewhere, something

that dissipates in direct gaze.

Where is the singer now?

How many drowned?

I need to write about something else

like mist after rain.

Helen Ivory, Constructing a Witch

Interspersed with collaged images and cut out poetry, the pieces in Constructing a Witch manage to be focussed yet wide ranging. What is is about women's bodies, blood, ageing flesh, feelings, sexuality... that over and over renders us dangerous, othered, monstrous? And what magic can we reach for to counter the tide of darkness in lives where all of us teeter on the edge of overwhelm?

The collection is an impressive feat of research brimming with references — Biblical, mediaeval, poetic, liteary and cultural... You will find here stories and atrocities, superstition and outrages, spells of resistance and musings on menopause, darkness and sisterhood... You will find rage and a linguistic dexterity that is as playful as it is serious. And you will find a vision for reclaiming narratives — from the opening 'The Awakening':

I hold up these rekindled women and we reel, we howl, and we shoot our filthy mouths off.

to' Some Definitions of a Witch' —

Gleaner of herbs

hallower of the compass.

Cunning hedge rider,

measurer of fire.

[...}

Practitioner of forgotten ways;

of rituals, sayer of spells.

Barefoot earth-listener,

older than God or television.

to the final poem 'The Spirit of the Storm'" —

There comes a point in every woman's life

when she transmutes into The Spirit of the Storm.

Why not grow snakes for hair,

conjure rain and lightning from your artful hands?

you will find the wrath that becomes the inevitable outcome of being, for centuries, misnamed.

Joshua Idehen, Songbook: collected works

A collected works in under a hundred pages that combine poetry, spoken word and lyrics from award-winning albums in the jazz/electronica genre, Songbook is a powerful collection. Idehen is a British-born Nigerian artist who lives in Sweden. The poems traverse geogrphies and media, each one finishing with a QR code so you can hear it as well as read it. Interrogating migration, colonialism, concepts of masculinity and what we mean by mental health and ways of healing, the poetry is vital and raw. It's alive with rhythm, bursting with humour, searingly honest and endlessly probing.

We know where we came from. We came on boats, on planes, with passports and on the back of trucks. We worked three jobs and sent the money back home. We brought our motherland to life in our kitchens, our bedrooms, our churches, our songs, our dance, our sex, our pidgin, our patois…

There's rage in these pages, but there's as much vulnerability and tenderness. There's darkness and provocation, but so much love and compassion.

So often song lyrics don't stand up as poetry — without the music, there's a depth missing that renders them all blunt surface — shiny and shallow. But this is not so with the poems in Songbooks, which have the energy of music contained in the lines and always a depth that bears re-reading. Even in the short pieces:

Prayer for Sad Times (Preservation Prayer)

I pray my

friends and their

friends stay alive

we fireworks

are due our Nov-

ember five

we have so much

loving to get back

to

Non-fiction

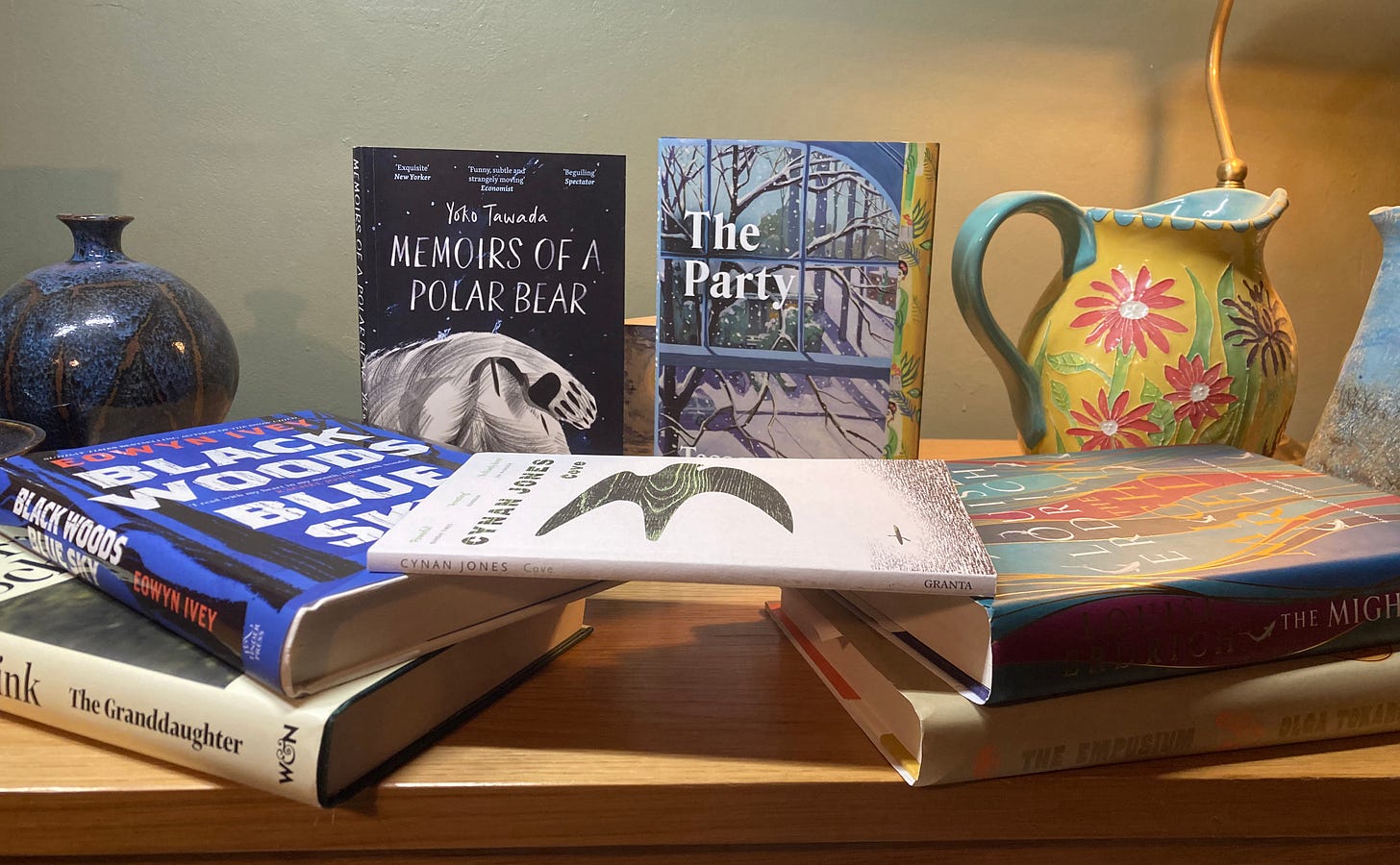

Sarah Roberts & Katy Siegel, Joan Mitchell

At Tate Modern there's a room of large canvasses by Gerhard Richter that I love -- they epitomise tranquility. They were painted to music by John Cage and form a six-part study. They're abstract paintings but my story-making mind finds latkes in them — serene and ethereal. It's the only abstract art I've ever loved. I can appreciate other pieces, but I struggle to locate an answering feeling.

Last autumn on a visit to the UK I saw a small selection of paintings by Joan Mitchell for the first time. And I was overwhelmed. There was a group of pastel drawings done in collaboration with poems, like James Shuyler's 'Daylight'

And when I thought

'Our love might end'

the sun went

right on shining

And a series of immense, vivid canvasses — all extraordinary, though 'Two Sunflowers' was the one I spent the longest with. The book on her work was a Christmas gift, an enormous tome that was an exercise in weight-lifting. and wonderful. It doesn't give a simple chronology of her life and work but uses a range of detailed, stimulating essays on themes to build the chronology. There are contributions from Paul Auster, the composer Gisèle Barneau, Am Rahn, Eileen Myles, Richard Shiff... building a multi-faceted portrait of the artist and her work and influences.

Joan Mitchell painted feelings evoked by landscapes. Her works are explosive, huge, intense, and heart-breakingly beautiful. The book is a fascinating read, but the large colour plates — 134 of them — plus copious colour figures throughout the text add so much to this generous, lively, intelligent discussion of an extrordinary painter and human who found inspiration in landscape, poetry, music... and made of it something supple and profound.

Painting is a means of feeling 'living'.

...I give gratitude to trees because they exist and that's all my painting is about.

Amy Liptrot, The Outrun

The Outrun follows a conventional journey narrative, in this case a story of struggling against alcohol addiction. But what makes it stand out is the author's engagement with the raw and beautiful landscapes of the Orkney Islands. Along the way Liptrot communicates with a sometimes savage vulnerability, interrogating her own self-destructiveness and the depths of her brokenness. And throughout this, the place she is from, the land, holds her, particularly when she moves out to a tiny island to live alone in a basic cottage.

The constant braiding of the islands and the human story, the subtle ways they mirror one another, build a sense of solace and the resilience. And into this weaving, there is another strand that is vital to Liptrot's recover — her constant engagement with technology. In one interview she says:

It’s really easy when talking and writing about digital tech to fall into this trap of being critical, saying these devices are making us disconnected from the outdoors and each other. I was very keen to not do that, I wanted to show - which is very much what I believe —that there are so many ways in which technology can connect people to the natural world.

I read the book on kindle while travelling and it’s is also a film, very much worth watching.

Seán Kissane, Karim Rehmani-White, Derek Jarman: Protest!

This massive book with its shiny black cover, huge red lettering and gold sparks arrived as an extraordinary Christmas present. It claims to be a definitive overview of the life and work of Derek Jarman and I'm not sure any book could encompass a person so fully, particularly someone of such range and scope in art and life, but it certainly gives a real sense of the vitality and scope of an amazing person.

In sections that cover Painting, Design, Super-8, Film making, Protest, Language and Nature, plus a comprehensive final chronology, a layered and complex picture of a life lived in art that encompassed activism and poetry, Bohemian London and gardening, queer punk and classical allusion... is explored through many lenses. The illustrations are lush and generous. There are interviews as well as short essays from people who knew Jarman in different contexts and times: John Maybury, Peter Tatchell, Philip Hoare, Sir Norman Rosenthal and Olivia Laing. And there are images from Jarman’s personal archives.

It's a book that is almost overwhelming in scope, but works because of that, building a larger than life portrat of someone who was deeply innovative, iconoclastic and brave. In a time of hateful and sensationalist media coverage (one doctor in a tabloid interview talked about having doubts about the 'ethical issue' of spending more researching drugs that might cure this 'gay diseases'!), Jarman was one of the first public figures to come out about being HIV positive. In his refusal to go quietly, he displayed extraordinary intelligence, wit and refusal to bow to fear and ignorance. And he did it with inimitable style and with the skill of the 'Renaissance person'.

One of his many legacies is the Jarman Now network — a movement to work with hospices based on the creative resilience Jarman showed in the face of terminal health. It's found a particular home in the Queer Grief group based at St Michael’s Hospice in St Leonard’s, East Sussex. There's also a Jarman Award for artist's using the moving image and his impact on conceptions of queer landscape continues to reverberate. I loved the book and I'm in awe of the person, but was also left wondering where now are the artists of this stature and range? It feels like the world could use some brave, inventive, unquiet artists in this moment too.

Virginia Woolf, Oh, to Be a Painter

This is a quirky and fascinating little book with a series of short essays that raise questions about the power of art to change us and how art relates to life, from the personal to the political. She begins in the National Portrait Gallery, wondering about the ability of portrait artists not to show us what someone looks like, but whether they can add anything to our estimate of the subjects' souls. And moves on to compare literary description and visual art, writers not faring as well in her estimation.

She considers the new art of cinema, which she describes as 'born fully clothed'"

It can say everything before it has anything to say

And she provides notes on two of Vanessa's Bell's exhibitions, noting how unusual it is for a woman to have exhibtions, and delving into the way her sister communicated emotion through objects as well as people.

Here, we cannot doubt as we look is somebody to whom the visible world has given a shock of emotion every day of the week. And she transmits it and makes us share it.

There is a longer conversation on Sickert. And a final essay on the artist and politics in which she exposes various possible attitudes towards art as useful (or not), and whether it is moral to make art in times of crisis when people could be serving society 'by making aeroplanes, by firing guns'. This, she concludes politicises artists, encouraging them to band together to protect their own survival and the survival of their art.

Nigel Slater, A Thousand Feasts

This is a thing of beauty to hold and a comforting gem to read. I read it slowly because each fragment tells of a meal, a place and its food, how food inhabits and changes a home, how objects associated with cooking resonate with us, musings on gardens and a final section of more miscellaneous musings which somethow make a fitting end...

Each entry is 1-3 pages and the prose is so sensual, the immersion in taste, colour, scent, atmosphere so immersive, that I found it impossible to read more than a handful at time... the way it's impossible to take in more than a couple of scents at once.

There is a huge amount of travel and an extraordinary array of food described. What I loved was the attention to the tiniest detail and to how grounded each entry felt, even when the subject matter was airy, because the sense of place or of objects always remains sharp. There is also so much emphasis on the joy and beauty of food not as fuel, but as nourishment on every level.

At the end of many of the short entries there's a tiny note, offset beneath a leaf motif and reading like a prose poem or prose haiku. I found myself often stopping to collect them in my journal:

Breakfast on the terrace, Lebanon. A square of white sheep's milk cheese on a white plate, moist, crumbly with the clean, sharp tang of sour milk. I trickle liquid honey over the craggy surface, letting it fall slowly from the spoon and watching it as it forms tiny pools of gold in the cheese's creases and dimples.

In Hokkaido, a tangle of wild mountain greens in tempura batter, presented on a disc of white paper, like a flower preserved in ice.

A bunch of dahlias in a jam jar, bright as a carnival, on a polished zinc table.

A meditative, soothing book that takes joy in small moments.

Margo Jefferson, Constructing a Nervous System

This is an extraordinary memoir — incisive, innovative, and moving. Her story is told in fragments that weave into the stories of black women — Ella Ftizgerald, Josephine Baker, Tina Turner, women in literature like Topsy in Uncle Tom's Cabin or in film, like Mammy in Gone With the Wind... She writes her story through her father's depression and its links to racism, through her sister's ballet lessons and through the way white singers and actors become the 'minstrels' of black people's exclusion.

She writes it through questions — what can a black female body be? Where can a black woman look for her reflection? How can black women find the gaps in culture, class, race and gender where a self might be constructed?

And she writes it through literary criticism — her analysis of Willa Cather's The Song of the Lark exposing the intricacies of

a work of art that enchants and erases her

And the many ways in which engaging in critique can become just another way to be excluded from cultural access and rendering herself 'damaged', someone to be 'pitied'...

She writes from the multiple selves that arise — from mixed ancestry, from crude definitions of race that both denigrate and appropriate culture, from how people find themselves adopting different personae in black or white settings...

I read the book in two sittings — breathless with admiration for her inventiveness and clarity. This is virtuoso story-telling. So much is not directly about herself, and yet the fragments and glimpses and crucial memories build a deep narrative. The tone is passionate, fierce, yet calm. The sentences are sharp. The effect is powerful.

John Burnside: Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction

There was something particulary poignant about reading Aurochs adn Auks less than a year since the poet, memoirist and essayist, John Burnside died. A poet of extraordinary sensibility whose urban childhood, overshadowed by violence and poverty, always informed his deep connections to the natural world, a constant search for enchantment, for 'glamourie'.

All of his work is characterised by deep imagination and vulnerability and if 'essays' sounds dry, then this could not be further from the truth. The themes of death and renewal explored in the book arose from his near-death experience during the pandemic. Aurochs were wild cattle, the origin of so many sacred images throughout Europe — Minotaur, Cretan bull dances, Spanish corrida traditions... The Great Auk, a strange bird that persisted into the mid-nineteenth century until human wiped them out, a rehearsal for so many extinctions.

Between and around their stories are explorations of what 'extinction' means and the authors account of almost dying from Covid, how such an experience forever changes our perspective on life...

In his third memoir, I Put a Spell on You, Burnside wrote

It might sound sentimental to say it, but we are blessed by the dead, and we know that we are, in spite of our protestations to the contrary. They leave spaces in our lives that, for some of us, are the closest thing to sacred we ever know. They are there and then they are gone and, after a time, we come to see a certain elegance in that—the elegance of a magic trick, say, where the conjurer rehearses the vanishing act that we must all accomplish sooner or later.

In Aurochs and Auks, we go on being blessed by the dead — by Burnside in particular. This is a prophetic, tender, beautiful short collection of essays with a clarion call to care, to connect.

Join me to write Calmly by Candlelight

In addition to seasonal writing workshops across 2025, I’m gathering with paid subscribers each month around the time of the dark moon to share a litle of our writing journey with some inspiration from a poem, time to write quietly (with a prompt from the poem or any writing you wish to bring) and a final inspiration to take away.

There are such riches of inspiration in what others have written and such riches in gathering to write. Even on Zoom, the sense of other presences supporting us as we write — whether from the prompt or something you bring yourself - is powerful.

The next Calmly by Candlelight writing gathering is on Sunday 27 April @ 8pm UK time and I’d love to meet you there.

The next writing workshop will be for the Beltane season, gathering on Wednesday 7 May.

If you don’t want to take out a paid subscription at the moment you can also support my work by buying me a herbal tea. It can be any amount from £4 and it’s a simple payment process — it’s a lovely way to offer occasional support for the work I’m doing without an ongoing commitment — just click on the image below

I love these lists, Jan. I've read Empusium and really enjoyed it. And now, I want to find some books on/by Derek Jarman as well as Virginia Woolf's small book (I'm reading The Waves right now). I was just lamenting our country's lack of trains to my husband the other day (as we prepare for a couple of weeks of a lot of driving). How nice it would be to be able to read and write and watch. Thank you!

I listened to The Mighty Red a couple of weeks ago and loved it. I love her writing, and am always amazed at how well her references to events like the financial crisis of 2008-2009 in this novel, hold up over time. My favorite part of this book was the relationship between Crystal and Kismet. I also loved the family and cultural history that informs the different characters' relationships to the town and the land. I also noticed how much and in how much detail meals and food preparation are described. Anyway, I thought it was brilliant. If you haven't read The Sentence, do, it's funny and brilliant as well.